Zinc: a trace-element with many benefits

Zinc is a very important trace-element involved in multiple processes in the human body.

It is mainly contained in the bones, teeth, hair, skin, liver, muscle - and in men - the testes.

Zinc is a component of several hundred enzymes including a large number of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) dehydrogenases, RNA and DNA polymerases, and DNA transcription factors, as well as alkaline phosphatase, superoxide dismutase and carbonic anhydrase (1).

In practical terms, European health authorities recognise that zinc helps protect cells against oxidative stress, and supports normal immune system function, DNA synthesis, cognitive function, fertility, testosterone levels, and skin, bones, nails and hair.

Zinc is popular with, amongst others, sportspeople, especially bodybuilders. It often features in cosmetic and/or dermatological products and even healing balms (2).

Symptoms of zinc deficiency

A lack of zinc can cause one or more of the following symptoms (3):

- diarrhoea;

- loss of appetite;

- open sores and wounds that don’t heal;

- sudden, unexplained weight loss;

- excessive sugar cravings;

- deterioration in mood (apathy);

- lack of concentration;

- prevalence of respiratory infections and immune dysfunction in general;

- decreased sense of taste and/or smell;

- night vision and eye health problems;

- erectile dysfunction in men;

- abnormal development of sex organs (in young people in the growth stage);

- decreased alertness;

- memory problems;

- delayed growth in children;

- complications in pregnancy;

- skin problems (acne);

- psoriasis;

- nail and hair loss.

However, these symptoms can also be caused by other deficiencies and diseases, so we’d recommend consulting a health professional for an accurate diagnosis if you are affected by any of them.

Lack of zinc: what are the causes?

As you might imagine, zinc deficiency is usually the result of under-consumption of foods that contain it.

However, it’s worth noting that certain groups of people are at higher risk of zinc deficiency:

- those taking diuretics or certain other medications (such as proton pump inhibitors);

- those suffering from diabetes mellitus, sickle cell disease, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, problems with alcohol consumption or malabsorption, and those who have undergone bariatric surgery;

- those who have suffered acute, serious, stressful health events (such as sepsis, burns or head trauma);

- elderly patients who are institutionalised or house-bound;

- pregnant women;

- those eating a vegetarian diet (or other restrictive diets).

Good to know: phytates reduce the bioavailability of zinc

Plant seeds contain phytate anions which are their primary means of storing phosphorus and minerals. But these phytates, or phytic acid, are considered anti-nutrients insofar as they make nutrients less bioavailable to the body, nutrients that include iron, calcium… and zinc (4)!

To reduce the phytate content of plant foods such as oilseeds and legumes, it’s important to pre-soak them and to eat them cooked or sprouted. This way, you’ll obtain the benefits of zinc, vegetarians included.

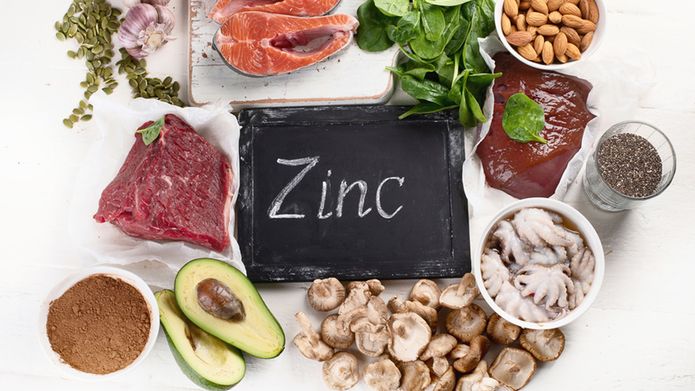

Zinc-rich foods

As is the case with iron, zinc from animal protein is more bioavailable, and the best dietary sources of zinc are all animal-source foods. Having said that, it’s entirely possible to meet your zinc requirements from a vegetarian diet, provided you follow the above-mentioned advice.

Here’s a list of the top zinc-rich foods in descending order (5) :

- oysters;

- calves’ liver;

- beef;

- veal;

- lamb;

- crab;

- crayfish;

- beef or pork liver;

- pork;

- egg yolk;

- wheatgerm;

- sesame seeds and tahini;

- clams;

- lobster;

- chicken;

- shiitake mushrooms;

- pumpkin seeds.

Which are the best zinc supplements for preventing deficiency?

Besides eating a balanced, high-protein diet, especially animal protein, you can ensure an adequate daily zinc intake by taking a dietary supplement.

There are various forms of zinc available in supplement form, including:

- zinc orotate: zinc can be combined with orotates, organic mineral salts found in dairy products, amongst others, which significantly increases its bioavailability (one such example is the product Zinc Orotate) (6);

- zinc methionine: zinc is also thought to be better absorbed when combined with the amino acid L-methionine. What’s more, this form may offer 4-6 times more antioxidant potency than standard zinc salts such as zinc oxide or zinc sulphate (one such supplement is L-OptiZinc®) (7);

- zinc L-carnosine: studies have for many years concluded that combining zinc with the amino acid L-carnosine may help protect the digestive system and reduce the discomfort of acid reflux (try Zinc L-Carnosine) (8-9);

- zinc bisglycinate: combining zinc with two glycine molecules improves the trace-element’s stability, protects it from stomach acidity and thus ensures optimal uptake (that’s precisely the case with Advanced Zinc Lozenges, an excellent zinc supplement in the form of suckable tablets).

SUPERSMART ADVICE

References

- PRASAD, A. S. Discovery and importance of zinc in human nutrition. In : Federation proceedings. 1984. p. 2829-2834.

- KHALED, S., BRUN, J. F., BARDET, L., et al.Importance physiologique du zinc dans l'activité physique. Science & sports, 1997, vol. 12, no 3, p. 179-191.

- CLASSEN, Hans-Georg, GRÖBER, Uwe, LÖW, Dieter, et al.Zinc deficiency. Symptoms, causes, diagnosis and therapy. Medizinische Monatsschrift fur Pharmazeuten, 2011, vol. 34, no 3, p. 87-95.

- WISE, A. Phytate and zinc bioavailability. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 1995, vol. 46, no 1, p. 53-63.

- SOLOMONS, Noel W. Dietary sources of zinc and factors affecting its bioavailability. Food and nutrition bulletin, 2001, vol. 22, no 2, p. 138-154.

- ANDERMANN, G. et DIETZ, M. The bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of three zinc salts: zinc pantothenate, zinc sulfate and zinc orotate. European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, 1982, vol. 7, no 3, p. 233-239.

- WEDEKIND, K. J., HORTIN, AEa, et BAKER, D. H. Methodology for assessing zinc bioavailability: efficacy estimates for zinc-methionine, zinc sulfate, and zinc oxide. Journal of animal science, 1992, vol. 70, no 1, p. 178-187.

- Choi H.S., Kim E.S., Keum B., Chun H.J., Sung M.-K. Betaine Chemistry, Analysis, Function and Effects. Royal Society of Chemistry; London, UK: 2015. L-Carnosine and Zinc in Gastric Protection; pp. 548–565.

- Mahmood A., FitzGerald A.J., Marchbank T., Ntatsaki E., Murray D., Ghosh S., Playford R.J. Zinc carnosine, a health food supplement that stabilises small bowel integrity and stimulates gut repair processes. 2007;56:168–175. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.099929.

- GANDIA, BOUR, MAURETTE, et al.A bioavailability study comparing two oral formulations containing zinc (Zn bis-glycinate vs. Zn gluconate) after a single administration to twelve healthy female volunteers. International journal for vitamin and nutrition research, 2007, vol. 77, no 4, p. 243-248.

56 Days

Very happy with the order and the…

Very happy with the order and the prompt team's response to an identified issue with my order.

KUQI Fatmir

63 Days

15 + years as a customer

I have been using their products for over 15 years as I find both the quality and pricing excellent.

Del Chandler

65 Days

Good quick delivery

Good quick delivery

Timothy O Shea

66 Days

Good service

Good communication following order. Product came within the time frame and was well packaged. The only confusing thing I found was in checking out. For some reason it is not clear how to do so and the current system should be improved.

Joe O Leary

75 Days

Simple and fast.

Simple and fast.

Nina

76 Days

Great product was definitely what is…

Great product was definitely what is says and arrived on without issue

customer

82 Days

I love reading those product facts on…

I love reading those product facts on Supersmart.com. Effective health products making permanent changes to my blood-work results and testes. However, I also have to order capsules from other websites.

NORDGULEN Olav

84 Days

Great products

Great products Very easy to choose, to order… and to get at home

Federica mastrojanni

87 Days

Service rapide et bons produits

Service rapide et bons produits

customer

88 Days

Good products and fast delivery

Good products and fast delivery

Trusted

93 Days

Does what it says on the can

I believe in this product Made to highest standard The ordering process is straightforward Delivery time prompt Excellent product, excellent service Happy customer ❤️

Sheba Kelleher

98 Days

Excellents produits

Excellents produits. Rien à dire si ce n'est qu'ils sont très chèrs.

MJS_France

100 Days

Very good supplement

Very good supplement

Glaveash

101 Days

Supersmart supplements are really…effective

Supersmart supplements are really effective and have helped me and family members and friends to improve their health including some of us with severe health problems including some with no existing medical treatment.

Anne Georget

103 Days

SuperBig Supersmart

SuperBig Supersmart

Pierre