Which types of protein are best for developing the glutes?

Do you long to have more rounded, shapely buttocks? Discover the best foods and protein sources for achieving a curvier bottom.

Adding mass to the glutes: a growing female trend

Beyoncé, Kim Kardashian, Nicki Minaj, Jennifer Lopez… So many stars have turned previously-accepted beauty standards on their head by making an asset of their ‘booty’! Long-disregarded as something to aspire to, fuller, rounded bottoms have now become cool, both on social media and in the gym.

This is reflected in a study published in 2020 by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS) which noted a 38.4% rise in buttock enhancement surgery during 2019.

Fortunately, ‘going under the knife’ is not the only way of boosting the size of your buttocks. You can do it by adjusting your diet, tweaking your exercise routine and optimising your results with tried-and-tested sources of protein. We’ll be your coach!

Which foods are best for increasing your glutes?

Let’s start with diet. The first step towards any gain in muscle mass (whether targeted at the glutes or not!), is to boost your protein intake. Protein helps to maintain and increase muscle mass and it’s therefore important to consume it in sufficient amounts (1). Studies suggest active individuals need a daily intake of 1.2-2g per kilo of bodyweight to increase muscle strength and volume (2).

With this in mind, try to alternate between animal protein (preferably lean white meat such as chicken or turkey, fish, eggs ...) and plant protein (soya, quinoa, lentils, nuts …), by varying your sources. If you’re a vegetarian, think about combining grains and pulses to ensure you obtain the whole range of essential amino acids (3).

In terms of dairy foods, ricotta is a good option as it is made from whey, a substance much-prized by bodybuilders!

At the same time, don’t forget about carbohydrates (fruit and wholegrain starches are best), and healthy fats(olive oil, rapeseed oil, oilseeds, oily fish rich in omega-3…) which influence the production of energy for muscles and counteract the process of catabolism (4-5).

For firm buttocks (with no ‘orange-peel’ skin), you also need nutrients that improve skin tissue quality . Fruits and vegetables such as kiwi, peppers, oranges and raw broccoli, contain significant levels of vitamin C which promotes normal collagen production (6), while cucumber (especially the skin), spinach and lettuce contain silicon which is involved in connective tissue structure (7).

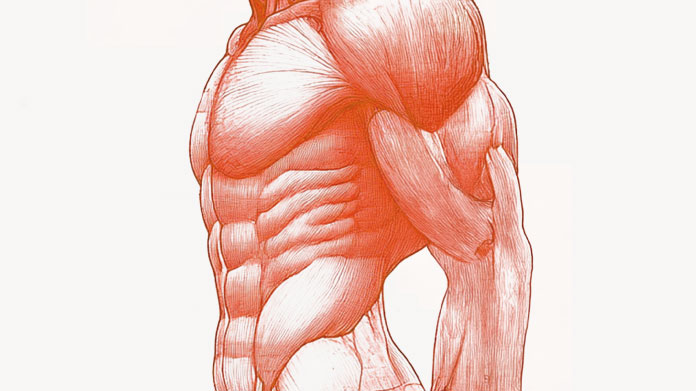

Boosting the glutes with strength training

Unsurprisingly, strength training is the best form of exercise for working and strengthening the glutes and ensuring shapely development. Ideally, you need a combination of concentric exercises (where the muscle fibres shorten) and eccentric exercises (where they stretch).

Among the most effective concentric exercises is the hip thrust: lying on your back, legs bent, raise your pelvis to form a straight line from the shoulders to the knees. Hold this position for a few seconds then release. The elevated glute bridge, where the feet are supported on a bench or chair, is a good variation as it produces maximum contractions. Quad extensions and cable pull-throughs also work the glutes and complement your training programme.

In terms of eccentric exercises, the ‘must-dos’ are repetitions of squats, deadlifts and lunges (and all their variations) which simultaneously work the glutes, hamstrings and back muscle groups (8).

One last point: it’s important to factor in sufficient recovery periods to allow muscle fibres to repair and rebuild. A regular training programme split into 2 to 4 sessions a week (depending on the volume-load you’ve set yourself) appears to be a good balance.

Which types of protein are best for growing the glutes?

Let’s be clear: there are no specific types of protein capable of initiating targeted glute hypertrophy. You can, however, draw on protein sources considered to be the ‘cornerstones’ of muscle-building to achieve fuller buttocks (in conjunction with a suitable training programme).

Containing all 9 amino acids essential for protein synthesis, whey protein (mentioned above) is a must (9). Obtained from whey, a by-product of cheese manufacture, it contains 80%-90% protein, with very few saturated fats, carbohydrates or lactose. Whey isolate, which is of higher quality than whey concentrate, has an even higher protein concentration and is more digestible.

Certain essential amino acids are also very popular at the moment with athletes looking to build muscle. These include the leucine-isoleucine-valine trio on which BCAA supplements are based. Providing the muscles with a source of instantly-usable energy (they’re broken down in muscle rather than in the liver), these branched-chain amino acids are associated with greater exercise tolerance and more efficient recovery (the supplement BCAA’s has the same 2:1:1 ratio between amino acids as that naturally present in meat) (10-11).

Stored in the form of phosphocreatine in muscle tissue, creatine is used for regenerating adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy used by muscles when they contract (12). While it does not directly create new muscle fibres, it helps to increase physical performance in repeated, short-duration, high-intensity exercise, thus maximising the benefits of training (the powdered supplement3-Creatine combines 3 active forms of creatine chosen for their excellent solubility and good digestive tolerance: creatine monohydrate, creatine phosphate and creatine pyruvate) (13).

L-glutamine is a non-essential amino acid popular in sports nutrition. In theory, the body is able to produce it from glutamic acid but reserves can be compromised by intense physical or mental stress, such as during over-training (14). This results in decreased muscle performance, a potential barrier to achieving your goals (after your glute-strengthening sessions, you could, for example, take L-Glutamine to promote effective recovery) (15).

SUPERSMART ADVICE

References

- Carbone JW, Pasiakos SM. Dietary Protein and Muscle Mass: Translating Science to Application and Health Benefit. 2019 May 22;11(5):1136. doi: 10.3390/nu11051136. PMID: 31121843; PMCID: PMC6566799.

- López-Martínez MI, Miguel M, Garcés-Rimón M. Protein and Sport: Alternative Sources and Strategies for Bioactive and Sustainable Sports Nutrition. Front Nutr. 2022 Jun 17;9:926043. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.926043. PMID: 35782926; PMCID: PMC9247391.

- Mariotti F, Gardner CD. Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets-A Review. 2019 Nov 4;11(11):2661. doi: 10.3390/nu11112661. PMID: 31690027; PMCID: PMC6893534.

- Lipina C, Hundal HS. Lipid modulation of skeletal muscle mass and function. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017 Apr;8(2):190-201. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12144. Epub 2016 Oct 8. PMID: 27897400; PMCID: PMC5377414.

- Børsheim E, Cree MG, Tipton KD, Elliott TA, Aarsland A, Wolfe RR. Effect of carbohydrate intake on net muscle protein synthesis during recovery from resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2004 Feb;96(2):674-8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00333.2003. Epub 2003 Oct 31. PMID: 14594866.

- Pullar JM, Carr AC, Vissers MCM. The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health. 2017 Aug 12;9(8):866. doi: 10.3390/nu9080866. PMID: 28805671; PMCID: PMC5579659.

- Jugdaohsingh R, Watson AI, Pedro LD, Powell JJ. The decrease in silicon concentration of the connective tissues with age in rats is a marker of connective tissue turnover. Bone. 2015 Jun;75:40-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.02.004. Epub 2015 Feb 14. PMID: 25687224; PMCID: PMC4406186.

- Neto WK, Soares EG, Vieira TL, Aguiar R, Chola TA, Sampaio VL, Gama EF. Gluteus Maximus Activation during Common Strength and Hypertrophy Exercises: A Systematic Review. J Sports Sci Med. 2020 Feb 24;19(1):195-203. PMID: 32132843; PMCID: PMC7039033.

- Duarte NM, Cruz AL, Silva DC, Cruz GM. Intake of whey isolate supplement and muscle mass gains in young healthy adults when combined with resistance training: a blinded randomized clinical trial (pilot study). J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2020 Jan;60(1):75-84. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.19.09741-X. Epub 2019 Sep 23. PMID: 31565912.

- VanDusseldorp TA, Escobar KA, Johnson KE, Stratton MT, Moriarty T, Cole N, McCormick JJ, Kerksick CM, Vaughan RA, Dokladny K, Kravitz L, Mermier CM. Effect of Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation on Recovery Following Acute Eccentric Exercise. 2018 Oct 1;10(10):1389. doi: 10.3390/nu10101389. PMID: 30275356; PMCID: PMC6212987.

- Khemtong C, Kuo CH, Chen CY, Jaime SJ, Condello G. Does Branched-Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs) Supplementation Attenuate Muscle Damage Markers and Soreness after Resistance Exercise in Trained Males? A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2021 May 31;13(6):1880. doi: 10.3390/nu13061880. PMID: 34072718; PMCID: PMC8230327.

- Kurosawa Y, Hamaoka T, Katsumura T, Kuwamori M, Kimura N, Sako T, Chance B. Creatine supplementation enhances anaerobic ATP synthesis during a single 10 sec maximal handgrip exercise. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003 Feb;244(1-2):105-12. PMID: 12701817.

- Wu SH, Chen KL, Hsu C, Chen HC, Chen JY, Yu SY, Shiu YJ. Creatine Supplementation for Muscle Growth: A Scoping Review of Randomized Clinical Trials from 2012 to 2021. 2022 Mar 16;14(6):1255. doi: 10.3390/nu14061255. PMID: 35334912; PMCID: PMC8949037.

- Baek JH, Jung S, Son H, Kang JS, Kim HJ. Glutamine Supplementation Prevents Chronic Stress-Induced Mild Cognitive Impairment. 2020 Mar 26;12(4):910. doi: 10.3390/nu12040910. PMID: 32224923; PMCID: PMC7230523.

- Córdova-Martínez A, Caballero-García A, Bello HJ, Pérez-Valdecantos D, Roche E. Effect of Glutamine Supplementation on Muscular Damage Biomarkers in Professional Basketball Players. 2021 Jun 17;13(6):2073. doi: 10.3390/nu13062073. PMID: 34204359; PMCID: PMC8234492.

Keywords

1 Days

Good quality product and customer service.

So far, I'm liking this product, and the customer service was very good.

ELZL

8 Days

The products I use are excel·lent

The products I use are excel·lent

ROSAS Josep Maria

16 Days

Delivery is prompt and I never saw a…

Delivery is prompt and I never saw a quality problem with the manufacturing. It is not possible to assess efficacy on a personal basis, since too many factors come into play. Efficacy can only be assessed statistically with a sufficient number of cases.

Roger De Backer

17 Days

I collaborates with the Supersmart…

I collaborates with the Supersmart more than 10 years. Every thing is going good. Quality of the things is good. Delivery comes in time. Five stars definitely !!!

Oleksiy

17 Days

All good

Simple, frictionless site, easy ordering, good delivery updates and execution.

Chris Robbins

19 Days

I feel better

I feel better

Peter Ammann

19 Days

Prompt delivery

Prompt delivery

JAKUB Radisch

21 Days

My new go-to for top quality supplements!

I am buying more and more of my supplements from this superb, high quality company. Cannot recommend it enough. Plus, excellent customer service with a quick, helpful team and speedy deliveries. Highly recommend Supersmart!

Cecilie H.

24 Days

SUPERSMART WHAT ELSE👍

SUPERSMART WHAT ELSE👍

DIEDERLE Christophe

27 Days

Excellent quality products with…

Excellent quality products with innovative formulas, as someone who has been suffering with acid reflux, these supplements have been lifesavers.

Oriana Moniz

27 Days

high quality supplement!

high quality supplement!

GALANT

28 Days

Good service prompt delivery

Good service prompt delivery

Mrs Marcella Reeves

33 Days

I like your clear explanation

I like your clear explanation. And how to make a choice of products for a specific health problem

Ingrid

39 Days

Great product and it arrives quickly.

Great product and it arrives quickly.

SOMMARIVA Gianni

40 Days

Excellent products and fast service.

Excellent products and fast service. What do we need more?

Margarida